Pakistan

Will the new broom sweep clean?

Lahore was clean. It is not so anymore. Lahore had a functioning waste management system. It is not so anymore. Lahore was envied by Karachi. It is not so anymore.

The road that led to this point is winding with twists and turns but not too long.

As begin most misadventures by this government, so did this one, with the positive intention of ending corruption and mismanagement inside Lahore Waste Management Corporation. Provincial Minister for Industries, Mian Aslam Iqbal, was given the additional charge of supervising waste management. Hearing of tales of corruption inside the LWMC, Aslam Iqbal sought written explanations. In reply, Chairman Amjad Ali Noon unleashed a barrage of accusations at the Minister himself. He sought time with the Chief Minister to complain about the matter. Unsuccessful in meeting Usman Buzdar, Amjad Ali Noon hit the jackpot when he met the Prime Minister himself. Till the last news poured in, Noon was not performing his departmental duties while Aslam Iqbal had restrained himself after the volley of attacks launched towards him.

There is still time for Chief Minister Usman Buzdar to take notice of the report handed over to him by the IT Department and the forensic report handed over to him by Auditor General’s office.

A problem that LWMC might have to confront sooner than later is that of the 14,000 workers enlisted under its banner, almost 5,000 are ghost employees. PSO provides almost 400,000 liters of fuel to LWMC, of which 315,000 liters are used while 85,000 liters remain unaccounted for. Who is hiding these details? And who will answer for the fact that appointments on higher positions were not made in a transparent manner? Where is the record for contracts given to private entities which would let us know at what rate is waste picked up from the city? What work were female socializers doing while they were hired to create awareness campaigns? Why was a war of allegations started as soon as a monitoring report was demanded? And why is the CFO reluctant to release the details of payments released to private firms?

Questions are being asked about why senatorial contracts were given at 59% higher than the set rates to a firm in Sargodha. About what is stopping Amjad Ali Noon and CEO Imran Ali Sultan are not acting on the forensics report themselves, which points the finger at many wrongdoings. And about who has threatened to file defamation suits, the details of which will be made public soon enough.

From 1947 till 1987, a team of 10,000 was employed to clean up the city. Daily wagers would look after a city of more than 3.5 million. Back then, Lahore was spread over 100 wards, dotted with an open drainage system. With time, the city was divided into zones. In 1990, eight deputy mayors were selected and 8 zones were carved out for them to govern.

In August 2001, the City District Government was founded, after which Lahore was divided into six towns, namely, Shalimar, Wagah, Daata, Gulberg, Nishtar and Iqbal Towns. After 2005, three more towns were added to the mic, Samanabad, Aziz Bhatti and Ravi Town.

Finally, in 2010, the Solid Waste Management Company came into being.

According to Aslam Iqbal, Lahore’s waste can be managed with just Rs. 7 billion per annum as opposed to the Rs 14 billion it is costing. If the employees hired for their jobs actually do what they are paid to, then the matter of ghost employees, too, can be settled. Vehicles can be monitored through video monitoring to cut down fudging in petrol allowances. LWMC can start the process of standing on its own feet instead of relying on foreign or private companies.

Lahore produces about 6,000 tons of waste daily. Corruption fudged this figure to 16,000 to 20,000 tons, costing billions more to the treasury.

Those in charge of cleaning the city are instead cleaning up the exchequer. Soon, Chief Minister Usman Buzdar may wake up from his slumber and dispatch these corrupt elements to the dustbin of history.

Regional

Cholera is making a comeback — and the world doesn’t have enough vaccines

“A billion people at risk”: How worldwide cholera outbreaks are threatening lives.

Amid a global resurgence of cholera, the world is fighting with one hand tied behind its back.

The global stockpile of the oral cholera vaccine — a supply whose needs are difficult to predict and fill anyway — has dwindled to nearly nothing after the Indian drug manufacturer that produced about 15 percent of the world’s supply stopped making the vaccine last year. While other companies are setting up new production capacity, the stockpile is now effectively nonexistent. Demand is so great that as soon as doses are produced, they must immediately ship to one of the world’s current cholera hot spots.

This crisis is symptomatic of a larger problem: the persistent lack of political will and financial investment to dramatically reduce cholera deaths.

Cholera flourishes in areas where there is contaminated water, poor sanitation, and people living in crowded conditions — like the city of Rafah, currently home to more than 1 million Palestinians displaced by Israel’s war in Gaza. Cholera has not yet been detected there, since no one from outside Gaza can bring it in, but an outbreak would be catastrophic given the decimation of Gaza’s health care system and the lack of access to humanitarian goods like clean water and medication.

The disease is typically spread when an infected person or people contaminate a water source by defecating in or near it. People get sick after drinking the contaminated water, suffering from acute diarrhea and vomiting — which can, without treatment, kill an infected person within a day.

It’s a disease that rich countries with clean water and good sanitation infrastructure do not have to worry about anymore. But cholera cases are rising worldwide now after a period of decline from 2017 through 2021, according to the World Health Organization’s cholera team leader Philippe Barboza. There are currently active cholera outbreaks in Zambia, Mozambique, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Ethiopia, Somalia, Zimbabwe, and Haiti.

“Once it is there in these situations, because of the very poor water and sanitation and hygiene situation, it can spread like wildfire,” Paul Spiegel, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Humanitarian Health, told Vox.

As many as 143,000 people die from this preventable disease each year — which could even be an underestimate, since some countries do not have the capacity to detect or compile data on cholera cases. According to some metrics, it is becoming more fatal because many infected people do not have adequate access to health care. Concurrent outbreaks throughout the world are straining the global health sector’s resources to respond.

“It’s a really horrible way to die,” Mohammad Fadlalla, an Ohio-based physician who volunteers with Medecins Sans Frontieres and has responded to multiple cholera outbreaks, told Vox.

With the increase in outbreaks and limited countermeasures, particularly vaccines, “We are talking about a billion people at risk” in the immediate term, Barboza said. “And this is an underestimate. This is a very conservative estimate.”

Why aren’t there enough cholera vaccine doses?

There are a few intersecting crises that have led to cholera’s comeback and the world’s limited capacity to combat it. One pivotal moment came in 2020, when Shantha (now Sanofi India), a fully owned subsidiary of French pharmaceutical company Sanofi based in India, announced that it would stop manufacturing its oral cholera vaccine at the end of 2022.

“We took this decision in a context where we were already producing very small volumes versus the total demand for cholera vaccines and in the knowledge that other cholera vaccine manufacturers (current and new entrants) had already announced an increased supply capacity in the years to come,” Sanofi told the Guardian in 2022.

The company said at the time that it had shared information about how its vaccine was manufactured with public health partners like the International Vaccine Institute (IVI), which has transferred the vaccine technology to new manufacturers.

But those contingencies weren’t enough to offset a total shutdown by the company that was manufacturing about 15 percent of the global vaccine supply depending on the year, as Jerome Kim, director general of the IVI, told Vox. That left just one other manufacturer, South Korea’s EuBiologics, in the market as global cholera cases surged.

“WHO has contacted [Sanofi] several times to ask first to increase [vaccine production], second to maintain, and third, to postpone their decision,” Barboza said. “So we have tried all the possible things and the rationale of [Sanofi is], ‘Oh, no, there will be other manufacturers that are coming.’”

In an email to Vox, Sanofi said that the decision to exit the cholera vaccine market was not about profitability, but rather based on an understanding that EuBiologics would increase its output and other manufacturers would enter the market.

EuBiologics will produce as many as 50 million doses of an oral cholera vaccine this year. The WHO announced in April that it approved a simplified, but still effective, version of the present formula for use, which will help mitigate the vaccine shortage.

The world has already been forced to start rationing vaccine doses. In 2022, the WHO recommended halving the vaccine dose from two to one, which downgrades the vaccine’s efficacy but does offer protection for a year or more, and obviously increases the number of people who can receive some protection with limited supplies. Last year, all of the 36 million regimens were distributed to 72 million people to take one dose each. Today, with only EuBiologics now producing a cholera vaccine, doses are allocated as soon as they are made to one of the areas with an active outbreak, said Derrick Sim, managing director of vaccine markets and health security at Gavi, the international vaccine alliance.

Because of the global shortfall, there are no vaccine doses available for preventive campaigns that would keep cholera out of communities in the first place. And absent an international commitment to improve the water supply and sanitation in poor countries at risk for cholera outbreaks — an approximately $114 billion yearly commitment — vaccination would be a powerful tool for preventing sickness and death from cholera in areas where outbreaks could occur.

There are some important developments in vaccine technology in the pipeline, such as a temperature-stable pill form that would be much easier to transport and administer than the current liquid form, which must be kept between 2 and 8 degrees Celsius. At least three companies are currently working to develop new cholera vaccines, but they won’t be on the market until at least the end of 2025, and potentially years later. Gavi, which supports vaccine programs in developing countries and has contributed to the vaccination of nearly 1 billion children since its founding in 2000, is also working with smaller manufacturers in developing countries in Africa to bolster the global supply and produce the vaccine closer to where it will ultimately be used, Sim said.

But developing cholera vaccines — from research to improve them to transferring the vaccine technology to new manufacturers, from clinical trials to purchasing and distributing them — also requires money. The WHO budgeted about $12 million for its cholera vaccination efforts last year, but that number will need to increase as cases do.

That could potentially help address some of these supply issues — but it also highlights why they exist in the first place.

“The big manufacturers are not interested in investing in a vaccine that only the poor countr[ies] can buy,” Barboza said, “and that will cost only $1.50 or $1 per dose.”

Why are cholera cases rising in the first place, in the 21st century no less?

At the time Sanofi decided to exit the cholera vaccine market in 2020, cholera was trending downward after a 20-year high in 2017. The Global Task Force for Cholera Control — a collaboration between the WHO, GAVI, and other stakeholders — had released a road map to reducing cholera deaths by 90 percent by 2030, and poor and developing countries where cholera is endemic or an active concern were implementing national cholera vaccination plans.

In retrospect, experts believe the world missed an opportunity to work aggressively toward prevention, an effort that would have been aided by Sanofi’s continued production of its cholera vaccines.

But Covid-19, which diverted resources and attention away from most other global diseases including cholera; an increase in displacement due to violence and conflict; and extreme weather events caused by climate change that both displace people and make environments more conducive to cholera have combined to allow the disease to spread more rapidly.

Four of the five worst years for cholera in recent history have come since 2017.

This is all the more concerning because cholera is fairly simple to prevent, with the supplies to provide clean drinking water and sanitation. It’s easy to treat, too: All it takes to cure cholera in most cases is clean water and oral rehydration salts, antibiotics in the worst-case scenarios. With proper medical intervention, no one should die from it.

In situations of extreme instability like in Sudan, or where the medical sector has been decimated as in Gaza, those interventions become more challenging.

And while some countries have long had routine cholera outbreaks, it’s not always easy to predict when or where they’ll hit, or how big they will grow, because contaminated water sources and infected people can cross borders, as likely occurred in Lebanon in 2022. Cholera is common in neighboring Syria, where the Assad regime has decimated local infrastructure and displaced hundreds of thousands of people. Though Lebanon had not experienced an outbreak since 1993, conditions were ripe for it. Years of government corruption and incompetence have led to a breakdown in public infrastructure including health care and sanitation — all of which helped trigger the outbreak in 2022. That outbreak saw at least 6,000 confirmed and suspectd cases.

In August 2023, Fadlalla was responding to an outbreak in Al Qadarif, Sudan, which has been in a devastating civil conflict for a year now.

“A lot of the governmental institutions were [at the time] eight months without their people getting paid their salaries, and the bureaucracy was not really functioning or operating,” he said. “And this is including the Ministries of Health. The whole medical sector was not getting paid, supplies were not getting restocked.”

Climate change and the conflict and displacement related to it also significantly contribute to the uptick in cholera outbreaks, according to experts Vox spoke with. Higher temperatures and changing weather patterns make the environmental conditions ripe for outbreaks in new places unused to the disease.

But climate change is not going to be reversed any time soon, nor is the global community going to commit to improving sanitation in developing countries or mitigating displacement. So in the meantime, vaccines remain one of the most important ways to prevent cholera deaths.

“It’s not that nothing is happening,” Barboza said. “There are a lot of things that are happening, but are they acting fast enough, with enough money?”

Business

Chinese textile delegation, APTMA resolve to explore possibilities of joint ventures

APTMA chief Kamran Arshad gives detailed presentation to the visiting delegation regarding the prospects of mutual cooperation in the textile industry of Pakistan

Lahore: Chinese textile machinery manufacturers and All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) leadership have resolved to explore possibilities of joint ventures in textile industry of Pakistan.

A delegation of Chinese textile machinery manufacturers visited APTMA and discussed in detail future prospects with regard to JVs with each other. Ms Wendy of M/s Guangdong Joint Era Digital Technology Co. Ltd. headed the delegation, which consisted of Mr Allen, Mr Amos, Ms Luya, Ms Louise, Mr Lucky, and Mr Haung.

Chairman APTMA Mr. Kamran Arshad welcomed the delegation at the APTMA. He was accompanied by zonal management committee members, Secretary General APTMA Mr. Mohammad Raza Baqir, Energy Advisor Mr. Tahir Basharat Cheema and other prominent textile exporters.

Speaking on the occasion, Ms Wendy said both China and Pakistan enjoy strong relations and China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is an example of this strong relationship. Both the countries have also good trade and cultural relations, she added.

She made a detailed presentation on the digital printing machine of their company to the APTMA members and hoped that their printing solutions would be helpful to the textile industry in Pakistan.

She also appreciated the investment-friendly environment in Pakistan and said that Chinese entrepreneurs are taking keen interest in enhancing business relationships with their Pakistani counterparts. She also invited APTMA members to visit China.

Chairman APTMA Mr. Kamran Arshad made a detailed presentation to the visiting delegation regarding the prospects of mutual cooperation in the textile industry of Pakistan.

Highlighting the preferential investment incentives, he said Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in different parts of Pakistan, especially under CPEC, are being offered for investment.

Mr. Kamran Arshad explained duty and tax exemption regime on import of plant, machinery and raw materials on investment made in SEZs.

He added any entity having investment of USD 50 million and more and land of at least 50 acres can request the government to give its industrial area status of a SEZ. He informed that two Chinese companies have already set up their own SEZs near Lahore.

Describing the significance of the industry, he said Pakistan is one of the few countries with a complete textile value chain starting from ginning, spinning, weaving, processing and garmenting.

Mr. Kamran Arshad also highlighted the benefits of China Pakistan Free Trade Agreement for exporters and importers as well as the investors.

Members of the Chinese delegation discussed and explored possibilities of joint ventures in textile industry, especially in the processing sector.

Secretary General APTMA Mr. Raza Baqir presented a vote of thanks to the visiting delegation at the end of the meeting.

Pakistan

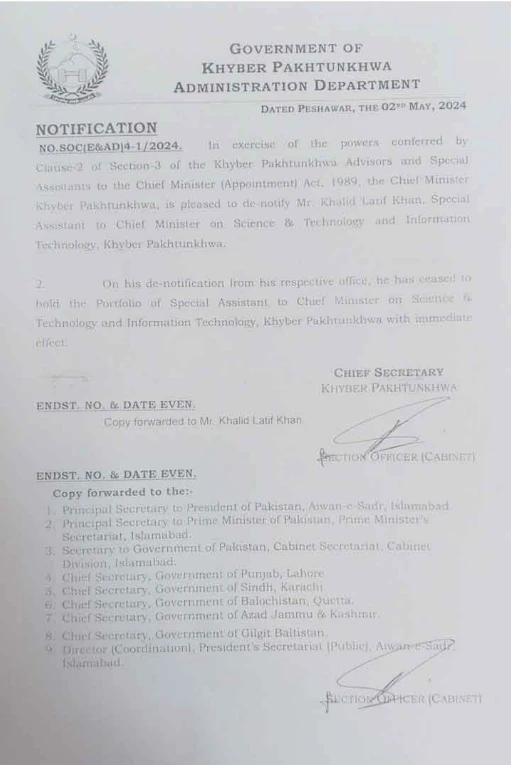

CM KP de-notifies Sher Afzal’s brother from post

Administration Department Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has also issued a de-notification notice to Special Assistant Khalid Latif Khan

Peshawar: Chief Minister Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Ali Amin Gandapur Friday removed his Special Assistant and National Assembly member Sher Afzal Marwat’s brother Khalid Latif Khan Marwat from the post.

In a statement issued by the KP government, it has been said that the Chief Minister has de-notified Khalid Latif Khan from the post of Special Assistant to the Chief Minister for Science and Technology and Information Technology using his constitutional powers.

Administration Department Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has also issued a de-notification notice to Special Assistant Khalid Latif Khan.

Earlier, reports were circulating that Chief Minister Gandapur had complained to Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) founder Imran Khan in Adiala Jail regarding Khalid Latif that he was interfering in various departments while Chief Minister had also criticized his performance.

On the other hand, differences emerged in the PTI when Khalid Latif Khan Marwart joined the KP cabinet.

-

Sports 1 day ago

Sports 1 day agoPakistani squad for Ireland, England series announced

-

Regional 2 days ago

Regional 2 days agoPunjab govt makes transfer, posting of senior officers

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoPM Shehbaz, Zardari pays tribute on Labour Day

-

Pakistan 1 day ago

Pakistan 1 day agoGovt releases funds to end current passport backlog

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoNawaz Sharif returns home after China tour

-

Technology 1 day ago

Technology 1 day agoAI could risk 17pc of jobs in Saudi Arabia: experts

-

Pakistan 2 days ago

Pakistan 2 days agoInterior Minister visits Pakistan Coast Guards’ headquarters

-

Pakistan 20 hours ago

Pakistan 20 hours agoPIA suspends flights to Dubai, Sharjah amid return of heavy rains